Make ARR Useful Again

What's the right way to track and report ARR and MRR? The speedrun team weighs in.

💡 This Week’s Big Ideas

🏘️ Madeline and Ben are building a reverse social network to restore the feeling of being part of a village. This is their story.

🔋 Jon Lai argues that “founder energy” can be a learned skill

💰 Andrew Chen says it’s a miracle VC works at all

📢 Bella Nazzari had a job opp for people who want to work in a sugar factory

💼 Join our talent network for more opportunities. If we see a fit for you, we'll intro you to relevant founders in the portfolio.

As a founder, your ARR (annual recurring revenue) and its monthly cousin MRR are among the most important metrics you’ll use to measure the health of your business. Investors and media care about the figure too, so founders can sometimes be tempted to adopt creative definitions and calculation methods when communicating ARR.

The most common sins of ARR calculation include:

annualizing a spiky month

counting usage surges as if they’ll recur forever

or sneaking one-time, non-predictable, or non-contractual fees into a “recurring” bucket.

The best definition of ARR isn’t the one that makes your fundraising deck look good. It’s the one that gives you the most insight into the current state of your company. Relying on overly creative definitions of ARR means your numbers are lying to you.

The best definition of ARR is one that helps you operate. If your ARR ticks up, can you explain which lever you pulled (pricing, packaging, activation, expansion) and predict next month’s number? That’s the only bar that matters. You maximize the business, not the metric.

With that in mind, it’s worth being definitive on these terms.

What revenue is, and what MRR and ARR are

GAAP revenue is the rule-bound number stamped and approved by your accountant. It’s pretty simple, you have revenue when you deliver the service. This is done ratably for classic subscriptions and by consumption for usage models.

MRR, by contrast, is a management metric. This is a point-in-time monthly value of recurring revenue you expect to keep happening. It’s tempting to say “ARR = 12 × MRR” and stop there. But that identity is only useful if “recurring” really means recurring—meaning you exclude one-offs (implementation, training, hardware) and you’re disciplined about usage. The clean approach is simple to state and powerful in practice. You should treat subscription and contracted minimums as MRR. Truly variable usage is its own line item and only when it proves stable or becomes contractually committed you can graduate it into MRR and ARR.

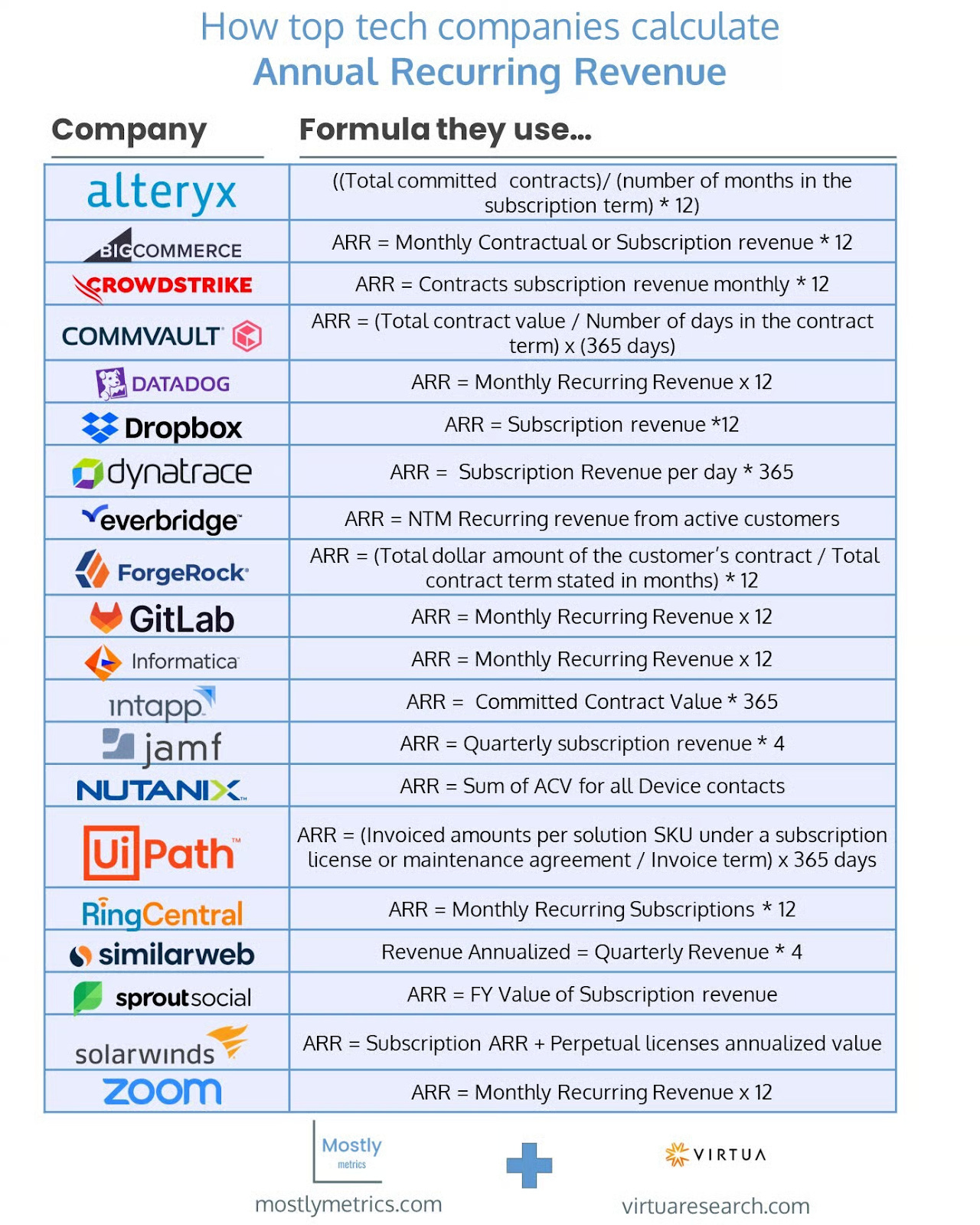

Still, there is lots of nuance that occurs, even in how public market companies, subject to stringent reporting requirements, treat ARR. An analysis by Mostly Metrics and Virtua Research found that there’s huge variation in the ways that top tech companies calculate it.

Among these definitions, we have no strong opinion which is best. And that’s the whole point! ARR is for you first and investors second. These examples are less commandments and more guardrails. Your MRR and ARR should reconcile, with a sensible lead/lag, to the way your model actually becomes GAAP revenue.

a16z speedrun General Manager Josh Lu says that founders should be aware that when you see large companies calculating ARR as MRRx12, their MRR is a lot more stable compared to startups. “Startups have spikier MRR,” Lu says. “MRR and MRR growth is all that matters, and reporting ARR as a brand new startup is kinda dumb.”

As Investment Partner Troy Kirwin points out, there’s also an unfortunate naming schema in the discourse where Annual Recurring Revenue (“ARR”) shares the same acronym as Annual Run Rate (Revenue), or as some founders mistakenly describe it, ‘ARR.’

“It’s important for founders to be VERY clear with how they are calculating ‘ARR’ in their decks or memos,” Kirwin says. “Unintentionally misleading investors with a blanket ‘ARR’ definition can lead to a breakage of trust.”

The AI wrinkle

AI inference takes every MRR bad habit and amplifies them. Demand is often bursty (launch weeks, seasonal spikes), units are tiny (per 1,000 tokens, per request), and capacity can be either provisioned or opportunistic. That means you need an MRR policy that respects how the infrastructure is priced.

A founder-practical way to handle this without twelve sub-metrics is to:

Keep MRR for the part of your AI product that is contracted with items like fixed subscription fees, platform access, support tiers, and committed throughput minimums. If a customer signs for a model unit per month or a token floor, that is MRR.

Track Measured Usage separately for everything else: pay-as-you-go tokens, burst capacity, overages. Report it every month with a trailing average. If usage stabilizes for, say, six months, you can promote it into MRR with a straight face.

Allow us to offer two addenda that will save you from heartache and audits from Deloitte:

First, resist the urge to smuggle multi-year step-ups into today’s topline. Calling exit-year contracted revenue your “MRR” makes you look bigger right now but won’t track to GAAP or cash, and sophisticated investors will haircut it anyway. Second, you should have a strong mental model for “MRR + measured usage” that translates into GAAP revenue each quarter.

Ultimately, ginning up investor hype using shaky metrics won’t make your company great. Define your MRR/ARR in such a way you can make smart choices, faster.

Like this post? Forward it to your team! For more weekly dives into the world of early stage startups, subscribe to our newsletter below.

This all makes sense for SaaS with steady renewal patterns, but it does not work for anything with natural seasonal or event-driven demand. The irony is that this was posted the day before Thanksgiving. Turkey demand is absolutely real, but nobody would annualize it using any of these metrics. Treating all spikes as artificial or misleading ignores entire categories of legitimate business cycles.